|

|

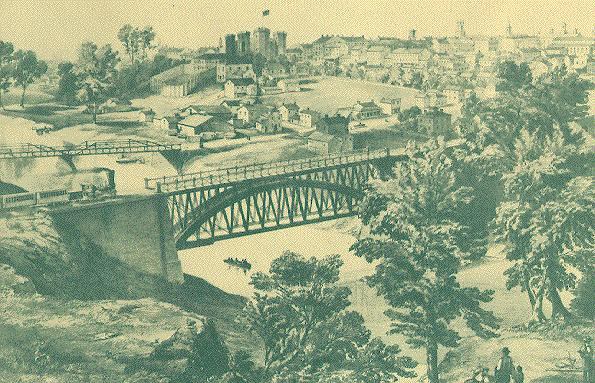

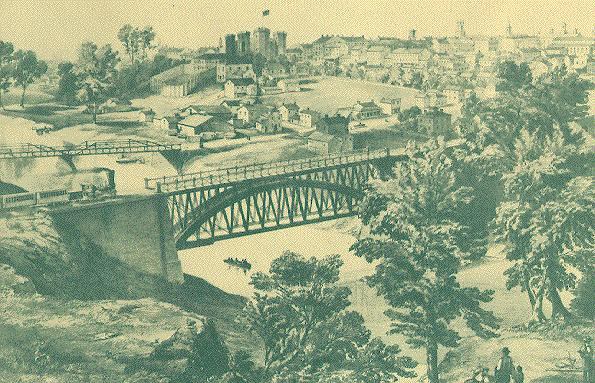

At the Forks of the ThamesAlthough the history of London begins in 1793, when Lieutenant-Governor John Graves Simcoe selected the Forks of the Thames as his choice for the future site for the capital of the province, the city proper was not founded until 1826. By that year the provincial capital had long been located at Toronto. What was still needed in the southwestern peninsula however, was an administrative seat for the vast London District which covered most of central Western Ontario. Vittoria, a little village in Norfolk County which had served as the district town for some years, had by 1825 become too remote from many of the little clusters of settlements which were gradually spreading north from Lake Erie. When the court house at Vittoria was ruined by fire, the legislature set up a committee to investigate the possibility of a new, more convenient location for the district town. A committee, presided over by Colonel Mahlon Burwell, was appointed to make the selection. Burwell was well qualified to advise on the region. He was the right hand man of Colonel Thomas Talbot, the chief colonizer of the western peninsula, and had surveyed much of the territory himself. The committee bypassed St. Thomas, which was as close to Lake Erie as Vittoria, and eventually decided on the Crown Reserve of land that Simcoe had, so many years before, set aside at the Forks of the Thames. Their choice was confirmed in a provincial statute which came into force on January 30, 1826. Then a local committee of magistrates, headed by Colonel Talbot himself, selected the present site of the Old Court House as the location for the government buildings. Burwell surveyed the town site, which covered the area now bounded on the south and west by the two branches of the Thames, roughly by Queens Avenue on the north and by Wellington Street on the east. A temporary court house was erected for the administration of the London District and work soon began on what is now the Old Court House. Gradually and unwillingly, for the Forks area was a wilderness, officials of the London District began to move to the new centre from their comfortable homes in Norfolk County. With them came merchants and hostelkeepers, including Dennis O'Brien, who was London's first storekeeper and George J. Goodhue, the first "Millionaire" of the city. Soon a cluster of buildings mushroomed around the court house square and the streets, loyally named after officials of the province and Great Britain, began to hum with life. The Bank of Upper Canada opened an office in the town and substantial brick stores began to make their appearance. In 1834 the Treasurer of the District, John Harris, erected the first elegant mansion, the nucleus of "Eldon House" of today. By that year the settlement had the 1,000 people needed to be made a separate parliamentary riding. In 1836 Lieutenant-Governor Sir Francis Bond Head, infamous for his part in the Mackenzie Rebellion, separated London from Middlesex and gave it its own member. Naturally, London voted Tory. When the Rebellion broke out in 1837, the local division of the Family Compact, the group which administered the province, held the town for the government without difficulty. Shortly the new Court House was bursting at the seams with the captured rebels. The Rebellion was one of the greatest stimulants to the evolution of London, for the British government decided to locate a garrison in the peninsula, which had been shaken by the Duncombe uprising and was threatened by invasion from the United States. Again London was chosen over St. Thomas, which was little eager to have an "unruly garrison". In 1838 the soldiers moved in and from then until 1869 there were generally troops stationed on what is now Victoria Park. This was another major factor in the making of London. While the choice as district town had meant administrative influence, the garrison rapidly brought military spending and a greatly increased population, both through the soldiers and their dependants and also through the larger number of civilians required to minister to their needs. By 1840 London was large enough to become an incorporated town (somewhat equal to a village today). The survey was extended east to include all the land to Adelaide Street, south to Trafalgar Street and north to Huron Street. The first council was elected and George J. Goodhue was chosen as first town president. Municipal services then began to appear and Covent Garden Market was established at its present location in 1845. By that time the advance of settlement in Western Ontario had necessitated the establishment of new administrative districts centred around Goderich, Woodstock and Simcoe. Yet the reduction in its administrative territory little affected the growth of London, for by the early 1840s the town was already beginning to establish a firm economic control over what is still today its hinterland. In its spread of commercial domination London was greatly aided by the efforts of its member of the Legislature, Hamilton H. Killaly, who directed his attention particularly to the improvement of the roads spreading out from his own riding. Communication to the north, the only direction that he missed, was quickly taken care of by the leading merchants, including John Labatt and Thomas Carling, who in the late 1840s constructed the Proof Line Road (now north Richmond Street and Highway 4) to connect London with its thirsty hinterland. Manufacturing also began to spring up, under the leadership of such figures as the tanners, Simeon Morrell and Ellis W. Hyman, and the iron founders Elijah Leonard and the McClary brothers. The prosperity of the town is well demonstrated by the fact that when fire struck in 1844 and 1845, nearly destroying its centre, rebuilding was instantaneous. In 1848 London was reincorporated with strengthened municipal powers and the population was shown by the census at 4,584. Following the fires further evidences of elegance made their appearance. Benjamin Cronyn, Anglican Rector of London since 1832, and his building committee engaged William Thomas of Toronto, one of Canada's greatest architects, to rebuild their church. The St. Paul's as designed by Thomas forms the nucleus of the Cathedral which still graces the city today. Thus, as the era of the iron horse burst upon Upper Canada, London was in an excellent position to ensure that the railway network of Western Ontario radiated from the city. Guided by the merchants the Great Western Railway line (now the Canadian National) was run through the middle of town, whereupon London entered into its liveliest period of expansion and land speculation. From December 15, 1853, when the first train steamed in from Hamilton, until the panic and depression of 1857, the city underwent a boom of building and land speculation. Such mansions as "Grosvenor Lodge" and "Locust Mount" were built, while the commercial interests could begin construction of the 'Tecumseh House", the largest hotel in British North America. In 1857 the Board of Trade, now the Chamber of Commerce, was established. The event which crowned London's prosperity was the incorporation of the town as a city, effective January 1, 1855. Murray Anderson, a tinsmith, was elected first mayor, and the council included such leading business figures as Thomas Carling and Elijah Leonard. The coat-of-arms, still the symbol of the city today, appropriately was topped by a railway engine belching smoke. Then suddenly, in 1857 it seemed that London's prosperity was to be wiped away by depression. But in 1861 London was rescued by the American Civil War. Located in a rich agricultural belt, the city was soon shipping the wheat of its hinterland to supply the Northern Army. Depression was supplanted by prosperity. Civil War affluence was soon evident in London's physical appearance. The erection of large downtown buildings began again and by the mid-1870s the centre of the city had assumed the shape it retained up until the 1960s. The decade of the 1870's also saw lines of new mansions rising along Queens and Grand Avenues, visible reflections of the city's new-found wealth. New institutions, such as the London Psychiatric Hospital and St. Joseph's Hospital came into being. Huron College was established in 1863 and the University of Western Ontario followed in 1878. Local financial institutions were founded simultaneously. By 1864 the merchants of the city were rich enough to form their own trust company, the Huron & Erie; life insurance companies followed with the founding of the London Life Insurance Company in 1874. The communications of the city were again being extended, both internally and externally. The London Street Railway was begun in 1873 and the modernization of the bridges began with the construction of the present Blackfriars Bridge in 1875. The telephone exchange appeared in 1879. Outside the city, the London, Huron & Bruce Railway was constructed to Wingham during 1871-75 and the present Canadian Pacific tracks followed across town a decade later. All these were factors which helped to consolidate the hold of the city over the region. 1. From this prosperous period, until the end of the century, London grew in size both geographically and demographically. Several of London's adjacent suburbs were annexed - London East in 1885, London South in 1890 and London West in 1898. Pottersburg, Ealing and Chelsea Green followed in 1912. In 1914, on the eve of World War I, London had reached a population of approximately 55,000 people. During the interwar period from 1918 to 1939, the city continued to grow steadily, although it was badly affected by the Great Depression. Several large buildings were constructed in this period - the Dominion Public Building on Richmond Street, the first buildings on the present campus of the University of Western Ontario, the Bell Telephone Building on Clarence Street and the London Life Insurance Company offices on Dufferin Avenue. Many new homes were built in London South and in the vicinity of Huron Street. A major flood struck London West in April, 1937. The water rose fifteen feet in only a few hours. Miraculously, only one resident was killed, though hundreds were left homeless. Since the end of World War II, London has experienced a growth unprecedented in its history. With the major annexation of 1961, which added 60,000 people to the city, London had grown close to a quarter of a million people in 1976, the one hundred and fiftieth anniversary of its founding. Major physical changes in London's appearance have occurred. In the old city core, many of the landmarks of the past have gone to be replaced by modern developments - the McClary factory was demolished for Wellington Square; the Hotel London was replaced by the City Centre; the Covent Garden Market was enclosed by the Market Garden Parking Building; and a new Court House was finally constructed on a demolished two block site. New suburbs have appeared on the outskirts-Lockwood Park, Sherwood Forest, Oakridge Acres. The old residential areas became threatened by the overuse of the automobile on streets meant only to accommodate horse and buggy. Recent planning decisions have, however, been carefully made to ensure that the character and integrity of the old city is maintained, something which can only result in enhancing the urban environment and in making London a pleasant place for its present and future citizens. 1. Frederick H. Armstrong and Daniel J. Brock, "Reflections on London's Past" (London, 1975), pp. 8-10 2. John H. Lutman, "The Historic Heart of London" (London, 1977), pp. 8 & 9 *Copyrighted by the City of London, 1995-2000 *Photograph provided by the London and Middlesex Historical Society |